Terrie Varnet, special needs planning attorney at Fletcher Tilton and a former educator and social worker, presented at the 2025 Academy of Special Needs Planners (ASNP) National Conference in San Diego last month in a session focused on working with clients to pursue public and private resources to foster independent living opportunities for adults with disabilities.

Terrie Varnet, special needs planning attorney at Fletcher Tilton and a former educator and social worker, presented at the 2025 Academy of Special Needs Planners (ASNP) National Conference in San Diego last month in a session focused on working with clients to pursue public and private resources to foster independent living opportunities for adults with disabilities.

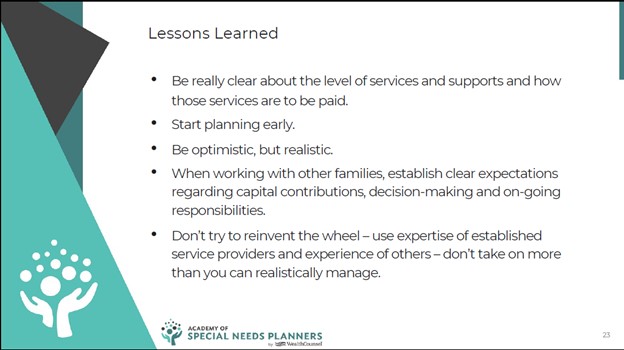

Drawing from her professional experience as well as her personal journey as a mother to Jennifer, her daughter who has cognitive disabilities, Varnet emphasized the importance of moving beyond traditional government-provided housing and services.

“We’re looking outside the box, not just looking at the government providing for your child or your family member but trying to pull together a plan where they can live independently in the community,” she said.

Recognizing the long waiting lists for government support, she urged the attorneys and financial planners in attendance to be open to exploring with their clients creative strategies that combine public and private resources.

Assessing Needs and Developing a Life Plan

A crucial first step, according to Varnet, is thoroughly assessing the unique skills and support needs of the individual with the disability who may be considering independent living options.

“You want to assess the skill level of the person who’s moving out. What are their skills, what are their abilities? And you have to determine what kind of services they need,” she said. “Because how can you come up with costs if you don’t know what services they’re going to need?”

This assessment can then inform the development of a realistic life plan that considers the individual’s own preferences as well as the contributions any family members or close friends are willing to make.

Varnet stressed the significance of involving the disabled individual in this planning process. Even for nonverbal individuals, she noted, careful observation can reveal their preferences for living arrangements.

“Self-advocates have a term that I love: 'Nothing about me without me,” she said. “It’s very, very important as you plan, as your clients plan, and as you help them plan, that you take a look at what that individual would like.”

Financial Planning and Government Benefits

Financial planning also plays a pivotal role in enabling independent living. For one, financial planners can evaluate the client’s life plan, work with them to identify government benefits for which they are eligible, and help the client determine how they might save money to fill in any gaps for services they may need to pay for privately.

Varnet also advised attendees to have their clients start early with saving and investing. She started saving money for Jennifer to live independently when her daughter was only 4 years old.

Varnet highlighted the need to leverage government benefits such as Medicaid waivers and Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI). Regarding SSDI, however, Varnet did caution against pushing adult children with a disability into full-time employment too quickly.

“When I see parents who are pushing for that full-time job when their adult child is maybe 22 or 23 years old, my advice to them is to start out part-time,” she said. “If the child succeeds, then you can start adding more hours to see if they can handle a full-time work week.”

She went on to discuss the complexities of Social Security rules and the potential impact of the disabled adult earning beyond Substantial Gainful Activity (SGA) limits. SSDI, she pointed out, is a program intended for people incapable of SGA. If the disabled individual has been working full time, they may lose out on qualifying for disabled adult child (DAC) benefits once their parents retire or pass away.

“That’s a lesson for us to learn,” she told attendees. “I’m not saying intentionally keep your child unemployed so they can keep future benefits. I’m saying be sure that this job has a future for them and it’s one that they can do continuously.”

Varnet also brought attention to the Military Child Protection Act, which can provide 55 percent of a veteran parent’s pension to a disabled adult child.

“I suggest putting this on your intake form and asking if your clients coming in are eligible for a military pension,” she said. “It’s something many of them aren't aware of.”

Housing Options

Next, Varnet covered various housing options beyond traditional group homes. These include shared living arrangements, where individuals share a home with support providers or roommates, and homeownership programs facilitated by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).

“HUD runs a program where they … work with banks and homes that have been foreclosed upon and sell them to somebody who qualifies, under HUD requirements, to purchase a home often for as little as what the old mortgage was,” she said.

She also mentioned the possibility of modifying an existing home or building an in-law apartment. One of her clients took their home and built an in-law apartment on the side of it that was approved for Section 8. Their two disabled sons lived there so that the family didn’t have to pay for 24/7 care.

Varnet encouraged attendees to research other programs that allow for home accommodations and modifications, noting that every state has a rehabilitation commission with programs that funds such adaptations.

Maximizing Private Resources

To supplement government benefits, Varnet suggested several strategies for maximizing private resources.

For example, she recommends a second-to-die life insurance policy placed in an irrevocable life insurance trust (ILIT). In her case, if she and her husband go into a nursing home, Varnet explained, the cash value of the policy would not count as theirs.

“The ILIT is Medicaid protection because it’s not my life insurance policy anymore; it belongs to the ILIT,” she said. It “creates a nice cushion of money.”

The ILIT that Varnet has in place is self-funding at this point because she started it when her daughter was young.

She also discussed the idea of having an adult disabled child living in their parent’s home pay rent, with the funds saved for future needs.

“What I used to do with Jennifer is I charged her rent for living in my home … I took that money. I didn’t need to charge Jennifer rent. She could have lived at my house for free; that would’ve been fine,” Varnet said. “But if I didn't charge her rent, No. 1, she’d have to engage in spend down every month and buy all kinds of junk that she didn’t need to stay under the $2,000 limit.”

Varnet then used part of that money to pay the premium on the second-to-die life insurance policy. She saved the remainder, which, when Jennifer moved out 10 years later, helped cover the costs for all the furnishings for Jennifer’s new home.

Real-Life Examples and State Variations

Varnet ended the session by sharing several real-life examples from her own practice of successful independent living arrangements. These included a sibling providing care to their disabled sister and receiving a stipend, a high-functioning adult who was able to live independently through a shared living arrangement with graduate students, as well as her own two disabled cousins who were able to live in their family home with live-in long-term support.

She point oout the wide variation in state Medicaid waiver programs and support services. “Unfortunately, there’s a patchwork quilt across America with the waiver programs. No two states are the same,” she said.

Regardless, she encouraged attendees to think creatively and collaborate with their clients and their families, as well as with other professionals, such as financial planners.

“Put your thinking caps on, use some of these ideas,” she said. “We don’t have to rely on the government 100 percent for our children if we are willing to take from the government whatever benefits are left and then plan earlier on so we can fill in the gaps.”

Check out other articles on sessions from this year’s ASNP National Conference: